Spanish Empire

Spain’s early support for the American Revolutionary War was marked by caution and secrecy as the Spanish sought to thoroughly prepare themselves before provoking their familiar enemy, the British. Determining the best moment for a war with the British was a lesson that the Spanish had bitterly learned earlier in the 18th century during the French and Indian War (1754-1763) as it was called in North America or the Seven Year’s War (1756-1763) as it was termed in Europe.

King Carlos III, who ruled Spain from 1759 to 1788 and during the years of the American Revolution, was an uncle to the French King Louis XVI, who also supported the rebels. Carlos III and Louis XVI were further united by a renewal of the third Bourbon Family Compact in 1762, in which they declared that the enemy of one of the Crowns would be the enemy of both – in other words, the British enemy, who were furious over the agreement.

King Carlos III authorized the declaration of war against the British to support the French in 1762. This entry into the Seven Years War was disastrous for the Spanish. Spain’s prized possessions from Havana, Cuba to Manila, Philippines were attacked and seized by the British. The financial losses and territorial losses were staggering. In the peace treaty of 1762, signed by Grimaldi, Spain lost its possessions in Florida, which had been occupied since the 16th century. The French gave New Orleans and the Louisiana territories to the Spanish as compensation.

In the late 1770s, when the harsh discussions of war once more echoed through the elegant marble palaces of Madrid, the Spanish remembered all too clearly the devastating losses of power, wealth and territories from their last conflict with the British. Spain had much to lose and much to protect in the dangerous period of empire building and global conflict that loomed again before them. This time, they determined that they would be wholly prepared for war on all fronts of their far-flung empire.

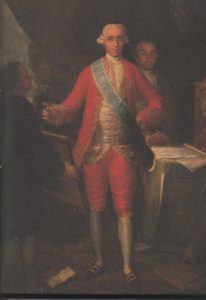

The King and his officials understood the importance of the North American rebellion to their own territories and to their ambitions to undermine the British, who had grown far too powerful from their successes in the Seven Year’s War. As the Secretary of State, José Moñino y Redondo, the Conde of Floridablanca, wrote in March of 1777, “the fate of the colonies interests us very much, and we shall do for them everything that circumstances permit….” (Image of Conde of Floridablanca)

The King and his officials understood the importance of the North American rebellion to their own territories and to their ambitions to undermine the British, who had grown far too powerful from their successes in the Seven Year’s War. As the Secretary of State, José Moñino y Redondo, the Conde of Floridablanca, wrote in March of 1777, “the fate of the colonies interests us very much, and we shall do for them everything that circumstances permit….” (Image of Conde of Floridablanca)

By June 1779, the Spanish were ready for war, and began military operations against the British in the Americas, from Pensacola, Florida, to San Carlos, Nicaragua. These battles diverted the British Army and Naval from fighting against the colonists, much to the relief of the Continental Army, which was losing in the southern United States.

Even in the sunset of their empire, the Spanish still had the financial power, productive capacity, armed forces, naval fleet, and economic strength to influence the outcome of the North American conflict towards victory or defeat. The decisions made and assistance given during our darkest hours helped to win the American Revolutionary War.