Mexico

Once upon a time in the United States of America, “Mexicans” crossing the border were welcome and celebrated. “Mexicans” circulated freely throughout the thirteen colonies, treasured in the businesses and homes that were fortunate enough to have them. Shortages of “Mexicans” were a severe problem, a constant and continual worry for the Continental Army. Many of the “Mexicans” were from Guanajuato, a state famous for an American Revolution later in the 20th century.

Once upon a time in the United States of America, “Mexicans” crossing the border were welcome and celebrated. “Mexicans” circulated freely throughout the thirteen colonies, treasured in the businesses and homes that were fortunate enough to have them. Shortages of “Mexicans” were a severe problem, a constant and continual worry for the Continental Army. Many of the “Mexicans” were from Guanajuato, a state famous for an American Revolution later in the 20th century.

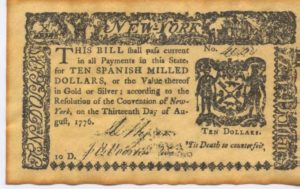

During the years of the American Revolutionary War in the 1770s, silver from the mines in Mexico reached the most rapid increases in over a century of production. Through this quadrupling of production, Mexico then accounted for 67% of all American output of silver. Guanajuato, the leading center, equaled the production of the entire viceroyalty of either Peru or La Plata. The silver coins were known as pieces of eight, pesos or “Mexicans”, and were used throughout the North American colonies. Even the British Army in North America paid their troops in silver pesos. In November 1776, several months after the Declaration of Independence, Congress adopted the silver peso as its standard of currency.

The explosion in silver production during those years resulted from improvements in fiscal incentives, government policies for commodity prices, the hard work of the Mexican, Bolivian, and Peruvian silver miners, and the management skills of the ‘silver kings’.

The refining and mining operations for mercury at the royal mill at Almaden were upgraded, enabling an increase in the mercury production that was essential to silver production. Jose de Gálvez, Minister of the Indies and uncle of Bernardo de Gálvez, further increased the incentives by halving the price of this essential ingredient and also reducing the price of gunpowder by a quarter.

The Mexican laborer population was increasing during this decade, and the diverse Mexican silver miners were a free, well-paid, and highly mobile labor force. In most camps, these miners earned a share of the silver ore in addition to their daily wage.

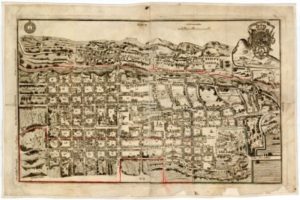

The ‘silver kings’ collaborated with merchant-capitalists to back ventures that often required years and sometimes decades of investment before yielding profit. An elaborate chain of credit stretched along the ‘silver road’ from the banks and merchant-financiers in Mexico City to local merchants and refiners in the leading camps who financed the actual miners. The scale of the Mexican enterprises rivaled enterprises across Europe. These men earned fabulous wealth that is still visible today in the colonial cities such as Querétaro and Guanajuato. (Image of Querétaro, 1796)

The ‘silver kings’ collaborated with merchant-capitalists to back ventures that often required years and sometimes decades of investment before yielding profit. An elaborate chain of credit stretched along the ‘silver road’ from the banks and merchant-financiers in Mexico City to local merchants and refiners in the leading camps who financed the actual miners. The scale of the Mexican enterprises rivaled enterprises across Europe. These men earned fabulous wealth that is still visible today in the colonial cities such as Querétaro and Guanajuato. (Image of Querétaro, 1796)

We can speculate as to the impact of this increase in silver production during the American Revolutionary War, when the colonies were desperate for hard currency. The Spanish pursued policies that deliberately allowed the North Americans to earn more of the silver that they needed: the North Americans were allowed to sell commodities such as flour in Havana, a leading international trade center. In turn, with the Mexican silver that the North Americans earned, they were able to purchase needed military supplies such as gunpowder on the world markets.